When we think about ageing, we often picture the surface: skin, hair, memory.

But beneath all of that lies the true story of decline: the loss of muscle and bone.

From around our mid 30s, we begin to lose 3-5% of muscle per decade, accelerating after 50. Bone follows a similar pattern, becoming lighter and more porous.

These changes are slow, invisible, and often dismissed as “getting older.”

But biologically, they are among the most powerful predictors of lifespan and healthspan.

Muscle mass, grip strength, and walking speed correlate more strongly with long-term survival than almost any blood test we run.

They are not vanity metrics, they are vital signs.

Strength is the language

of longevity

Muscle: more than movement

When we think about ageing, we often picture the surface — skin, hair, memory.

But beneath all of that lies the true story of decline: the loss of muscle and bone.

From around our mid 30s, we begin to lose 3-5% of muscle per decade, accelerating after 50. Bone follows a similar pattern, becoming lighter and more porous.

These changes are slow, invisible, and often dismissed as “getting older.”

But biologically, they are among the most powerful predictors of lifespan and healthspan.

Muscle mass, grip strength, and walking speed correlate more strongly with long-term survival than almost any blood test we run.

They are not vanity metrics, they are vital signs.

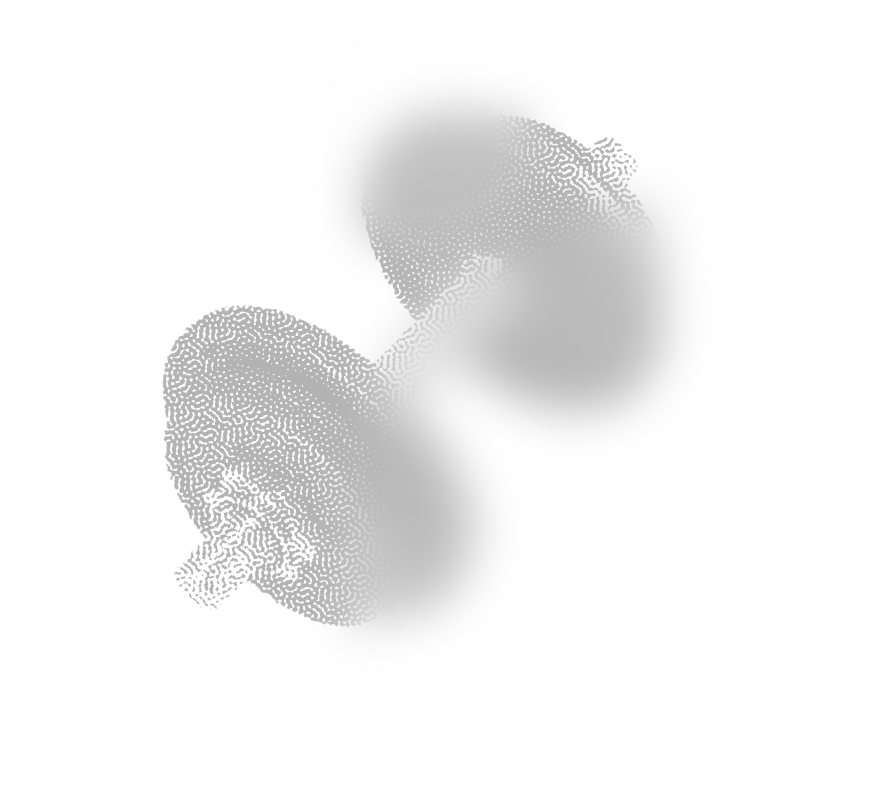

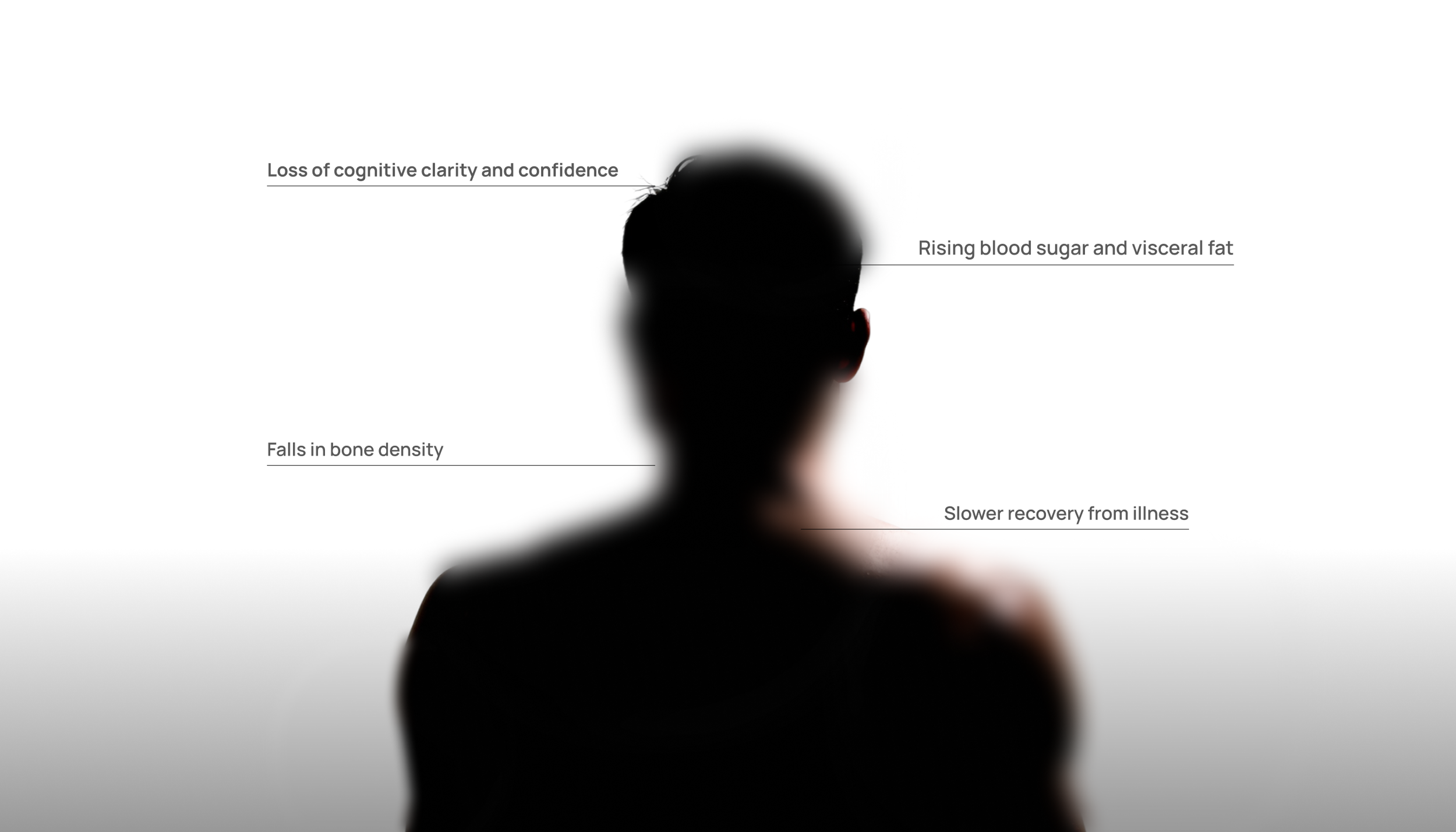

When muscle declines, we see:

The loss of muscle mass leads to higher blood sugar and visceral fat, slower recovery from illness, a gradual decrease in bone density, and a decline in mental clarity and confidence. Rebuilding muscle is not about appearance, it’s a form of preventive medicine.

Bone isn’t static. It is a living, dynamic tissue that responds to stress, movement, and nutrition.

The moment we stop loading it, it starts thinning.

That process speeds up dramatically in women after menopause and in men with low activity or hormonal drift.

Fractures in later life are rarely random; they’re the result of years of under-stimulation and under-nutrition.

Bone density can be stabilised, even improved, with resistance training, sufficient protein, vitamin D sufficiency, and micronutrients like calcium, magnesium, and vitamin K2 (where indicated).

Movement is the stimulus; nutrition is the scaffold; rest is the integration.

Bone: the silent structure of resilience

The architecture of functional ageing

Functional ageing is not about staying fit. It is about preserving physical capability, independence and quality of life over time.

Being functionally fit means being able to climb stairs, carry groceries, get up from the floor and move through daily life without assistance. Exercise helps protect these abilities as we age.

Core foundations of functional ageing:

Strength training: Progressive resistance training two to three times per week supports muscle mass, bone density and overall strength.

Endurance training: Aerobic exercise maintains cardiovascular health and long term energy production.

Balance and mobility training: Balance and mobility work improves coordination, joint health and postural control, reducing the risk of falls.

Recovery and regeneration: Adequate sleep and sufficient protein intake allow the body to adapt and remain resilient.

Exercise is not about chasing numbers. It is about protecting independence.

Weekly exercise portfolio:

A well structured weekly programme should include all key exercise domains to support health, longevity and functional performance.

VO₂ max training: One session per week focused on maximal aerobic capacity, typically four to five intervals of four to eight minutes at eighty to ninety five percent of maximum heart rate.

Functional fitness training: One to two sessions per week combining strength and endurance through mixed intensity formats such as functional circuits or CrossFit and Hyrox style training.

Zone 2 aerobic training: Three sessions per week of at least forty five minutes at sixty five to seventy five percent of maximum heart rate, using activities such as walking, jogging, cycling, swimming or rowing.

Strength, balance and mobility work: Integrated across the week to support movement quality, joint health and long term sustainability.

Why this approach works:

Combining all exercise domains within a weekly structure builds a resilient body that performs in training and everyday life, supporting healthy ageing and long term independence.

How much is enough?

There’s no single formula, but for most people the sweet spot lies between 150-300 minutes of moderate movement per week, including two dedicated strength sessions.

Even small doses matter, ten minutes of walking after meals, squats before breakfast, carrying groceries instead of rolling them.

The body keeps score.

It doesn’t care if you trained for an hour or lifted your child, it just responds to load, oxygen, and intention.

The muscle – brain connection

Strength training does more than protect joints; it protects cognition.

Multiple studies show that resistance exercise improves executive function and slows age-related brain changes.

Muscle produces growth factors that cross the blood–brain barrier, stimulating neurogenesis and reducing inflammation.

Every time you lift a weight, you are also lifting the brain.

Nutrition’s role in strength and bone maintenance

Protein: aim for 1.6–2.2 g/kg/day; distribute evenly across meals.

Calcium and vitamin D: foundational for bone, especially in post-menopause or reduced sunlight exposure.

Micronutrients: magnesium, vitamin K2, and omega-3s support bone remodelling and anti-inflammatory balance.

Hydration: essential for muscle contraction and recovery.

Without fuel, even the best training is wasted adaptation.

At the Longevity Medicine Institute, we treat muscle and bone as trackable biomarkers.

We measure:

DEXA (bone density and body composition)

Grip strength

VO₂ max and recovery rate

Functional movement and gait

Biomarkers of inflammation, vitamin D, and bone turnover

Data makes motivation objective.

It turns exercise into a prescription with measurable returns.

Measuring progress

The truth

The strongest predictor of longevity isn’t how young you look, it’s how strong you stay.

Muscle and bone are the physical memory of how well you’ve lived: the meals, the walks, the sleep, the discipline, the small acts repeated.

Build them early.

Protect them always.

They are the currency of a long, independent life.

Every patient I’ve seen who has aged well, truly well, has one thing in common: they never stopped moving.

Not necessarily running marathons or lifting heavy weights, but they kept using their body with intent.

Strength is the quiet foundation of resilience. It protects the brain, the heart, the bones, and the sense of autonomy that defines a long life.

When you train muscle, you’re training your metabolism, your mood, and your confidence all at once.

If you could put the benefits of consistent resistance and movement into a pill, it would be the most powerful longevity drug ever created and yet it costs nothing but time and attention.

I don’t see exercise as “fitness.” I see it as future proofing, the simplest way to make sure that your final decades remain strong, independent, and clear minded.

That’s what longevity really means to me.