Emotional stability is not a personality trait, it’s a physiological state.

Our brain, endocrine system, immune system and gut form one continuous network of feedback. When stress is acute and brief, that system strengthens. When it’s persistent, the communication lines begin to fray.

Chronically elevated stress hormones, particularly cortisol and adrenaline, alter glucose control, raise blood pressure, blunt immune regulation and accelerate inflammatory ageing. Over years, this becomes visible as poor sleep, weight fluctuation, fatigue, anxiety, and cognitive decline.

Longevity medicine treats emotional wellbeing as biology, not psychology alone. It’s about re-establishing rhythm between activation and recovery, the daily oscillation that lets the body repair itself.

The biology of how we cope

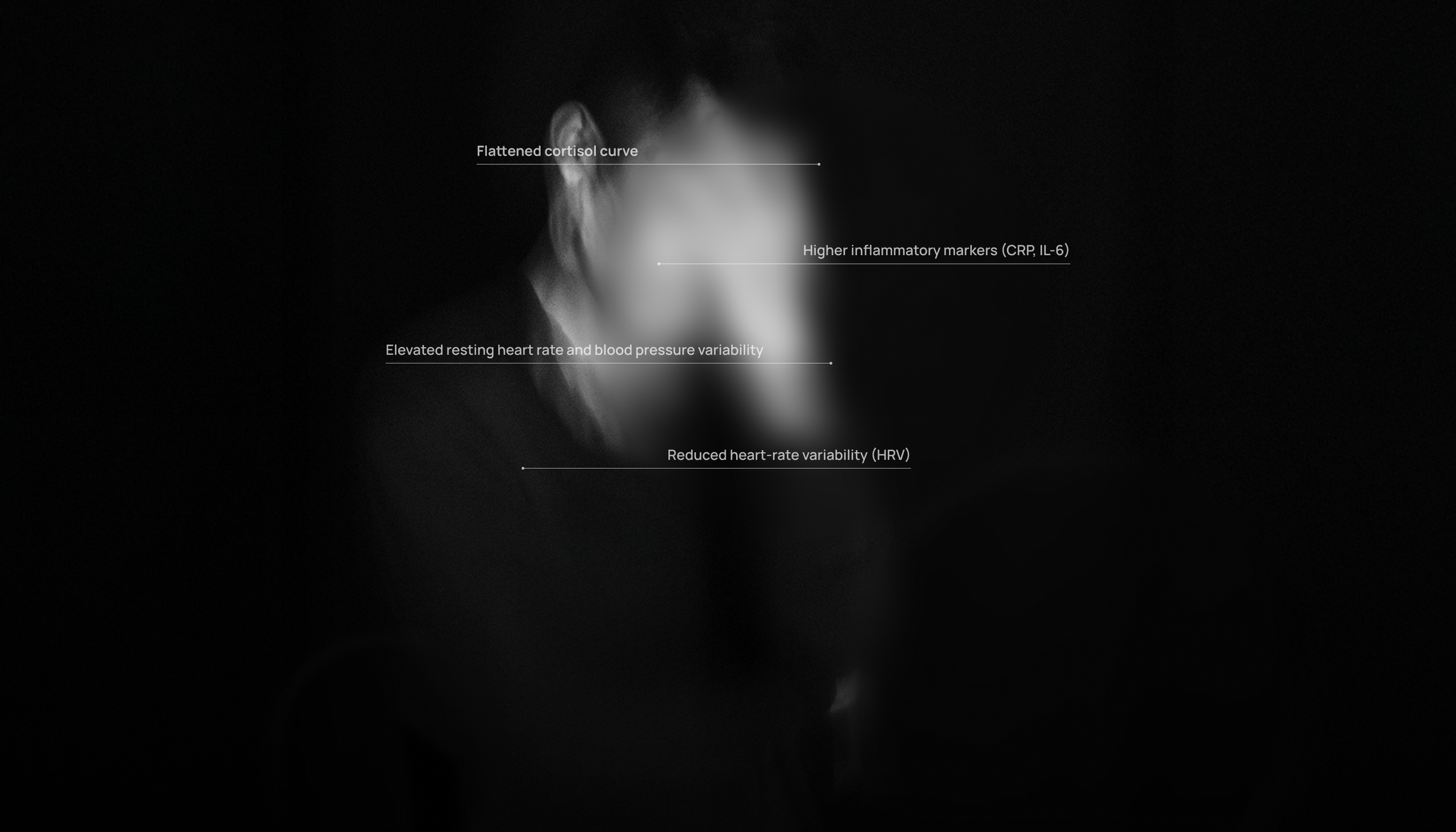

What stress looks like in data

When patients feel “wired but tired,” we often see the same physiological fingerprints: reduced heart-rate variability, indicating autonomic rigidity; elevated resting heart rate and fluctuations in blood pressure; a flattened cortisol curve, low in the morning and high at night; higher levels of inflammatory markers such as CRP and IL-6, often accompanied by disrupted lipid profiles; poor sleep efficiency with shortened deep-sleep phases; and an increase in visceral fat alongside reduced insulin sensitivity.

These aren’t abstract ideas

they’re measurable signs that the

stress - recovery cycle is breaking down.

Restoring regulation

The aim isn’t to eliminate stress; it’s to rebuild adaptability.

That adaptability is created through four levers:

1. Sleep rhythm

Consistent wake and sleep times, aligned with light exposure, reset hormonal timing and lower nightly cortisol. Treat sleep as a biological appointment, not an optional luxury.

3. Metabolic stability

Stable glucose, adequate protein, and reduced alcohol protect the brain from volatile energy swings that mimic anxiety. What appears “psychological” often starts as fuel instability.

2. Physical conditioning

Regular aerobic activity and resistance training remodel the stress-response system itself, lowering baseline adrenaline, improving HRV, and increasing resilience to future challenges.

4. Cognitive workload

Structured breaks, focused work blocks, and deliberate decompression periods maintain prefrontal function. Without recovery, cognitive control erodes and emotion dominates decision-making.

The gut - brain - immune axis

Seventy percent of the body’s immune cells live around the intestine. When stress disrupts the gut barrier or microbial diversity, inflammation feeds back to the brain, altering mood and sleep.

Supporting gut health through fibre diversity, fermented foods, and reduced ultra-processed intake improves not just digestion, but emotional tone and immune control.

Objective tools I use in practice

Heart-rate variability (HRV) and resting heart rate should be monitored over several weeks to reveal meaningful trends rather than short term fluctuations. Observing blood pressure patterns throughout the day particularly the difference between morning and evening values provides additional insight into autonomic balance. Laboratory measures such as hs-CRP and fasting insulin help assess systemic inflammation and metabolic regulation.

When indicated, sleep architecture can be evaluated through wearable technology or polysomnography to identify disruptions in restorative rest. Body composition and visceral fat, measured via DEXA, further clarify the physiological impact of chronic stress. Together, these parameters transform stress management from vague guidance into a measurable, data-driven aspect of preventive medicine.

Interventions when stress

becomes disease

When persistent anxiety, depression, insomnia or burnout develop, behavioural and psychological therapies are often the most effective first-line treatments.

Where symptoms remain severe or risk factors escalate, medical therapy may be indicated, always prescribed and monitored by a qualified practitioner.

The principle is integration: biological, psychological and social domains treated together, with measurable outcomes.

What improvement

feels like

Recovery shows itself as better concentration, steadier mood, stronger exercise output, deeper sleep, and the ability to calm quickly after provocation.

In data terms: HRV rises, CRP falls, glucose stabilises, resting heart rate drops.

In real life: you feel more capable, not just more relaxed.

“The longer I practice, the clearer it becomes that emotional regulation is the quiet determinant of healthspan.

You can optimise blood tests, train hard, eat perfectly, but if your nervous system never down shifts, biology will keep the score.

The most resilient people I meet aren’t those with easy lives; they’re the ones who recover fully between challenges.

For me, emotional wellbeing is the daily proof that your physiology and psychology are working together.

That’s what real longevity looks like, not absence of stress, but balance restored.”